Imagine opening a paper (yeah, I know, harder & harder to imagine), or following a link, and reading in the first paragraph you see something along the lines of: ‘God, what is it with drivers? Don’t they sometimes make you want to just drop a breeze block off a motorway bridge and listen for the smash?’. Hilarious, no?

Rod Liddle, in The Times, on May 24 2020:

Every day it’s the same. Walk out of my front door with the dog to be swept aside, into a hedge, by a middle-class family from the city who think they’re all Bradley bloody Wiggins. Daddy and Piers, 11, in the peloton. Mummy bringing up the rear with little Poppy, 6, and Oliver, 4. All in Lycra, all with their energy drinks and fatuous expressions on their faces, expressions of self-righteousness and irreproachable virtue. This is a local lane for local people — go back to your tenements, I shout at them. My wife has persuaded me that, strictly speaking, it is against the law to tie piano wire at neck height across the road. Oh, but it’s tempting.

Rod Liddle, The Sunday Times, 24 May 2020

Don’t forget Rod Liddle in 2016:

At last we have a transport secretary prepared to take the menace of cyclists seriously. Chris Grayling opened the door of his ministerial car to knock one off his bike — a beautifully timed manoeuvre. Grayling then leant over the prone and whimpering Jaiqi Liu and told him he’d been cycling too fast. Respect! The cyclist had been “undertaking” — a practice enjoyed by many cyclists that, while not illegal, is discouraged in the Highway Code.

Grayling devised a suitable method of discouragement. When in London I repeatedly open and close the door of my taxi to try to catch one of them at it and send him flying. I like to think I’m doing my bit to make London a safer place for normal humans.

Rod Liddle, The Sunday Times, 18 December 2016

This earlier (and error-ridden – ‘undertaking’?) article was, according to a backpedalling Liddle afterwards, written with ‘heavy irony’. That would be irony so dense and weighty that it plummets straight to earth, crushing plausible deniability underneath it on the way.

But then, it’s always ‘just a laugh’, this kind of thing. All the way back to Matthew Parris in 2009, also writing in The Times and calling for the decapitation of cyclists with the assistance of piano wire (similar methods are regularly used to injure mountain bikers and leisure cyclists in the UK). When it’s cyclists in the frame, people’s appetite for comedy seems endless. Even if the same – obviously entirely unserious and entirely harmless – ‘observations’ seem to get recycled a lot.

Admittedly it’s not just a one-note melody. As well as jokily and non-seriously advocating killing people on bikes because they are all gay-lycra-pedo-nonces, some observers jokily and non-seriously advocate murdering people on bikes because they aren’t human.

But all those promises to ‘absolutely murder’, ‘mow down’ and ‘wipe out’ people on bikes must surely be part of the joke, something like a punchline, as with Liddle’s fantasy about dooring a passing cyclist? Alongside all this weirdly intense, widely shared and somewhat obsessive-appearing ‘humour’, it’s hardly surprising to find that so many comments under stories about cyclists getting injured and killed on the road opine that it was obviously their fault that they got hurt or killed.

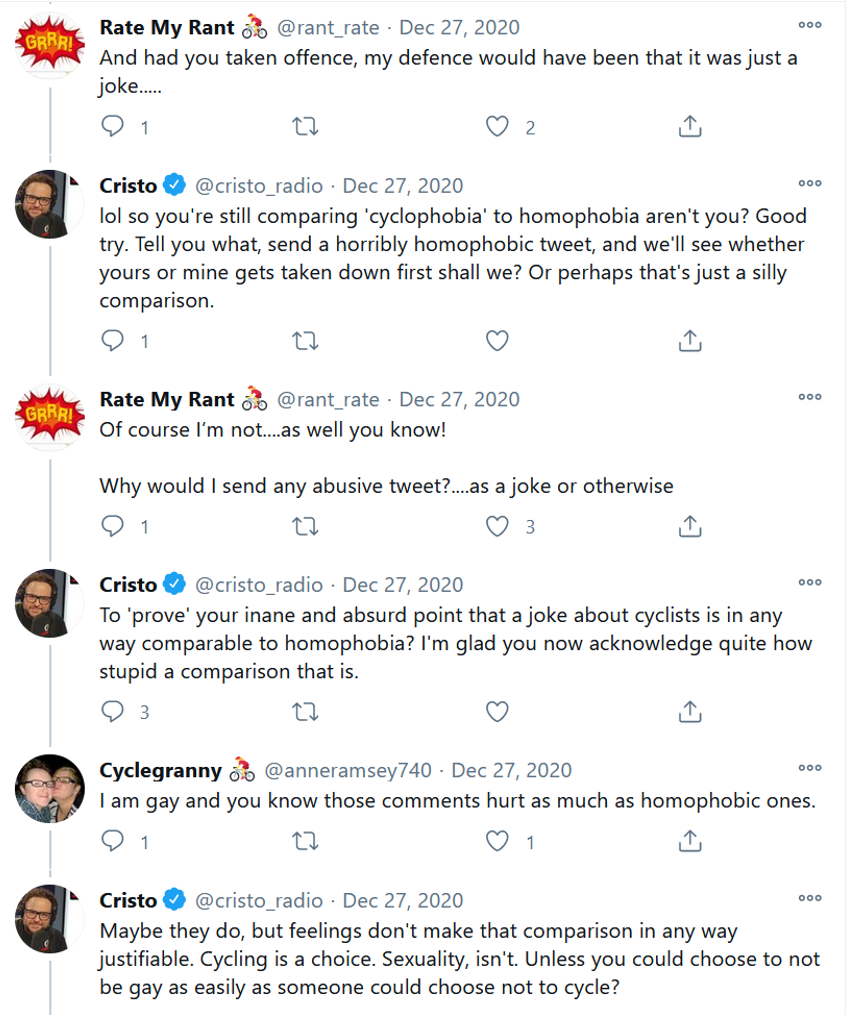

So what can we make of all this widely-shared dislike and denigration? It’s interesting what happens when people try to make links between prejudice towards cyclists and other forms of prejudice. Without wanting to spread around any insinuation of guilt by association, here’s a tweet from radio personality Christo Foufas, who often tweets about cyclists and the new cycling infrastructure being built in London.

The line here is a familiar one, connected to Cristo’s invective against protected cycle lanes, and indeed against any provisions directly designed to make cycling safer. Cyclists, according to the Cristo line, are members of a chippy, uppity, fuzzily-defined ‘elite’ who demand favourable treatment while not ‘paying their way’, and indeed flouting traffic laws at every opportunity to boot.

The ‘debate’ then triggered by what Christo immediately referred to as a ‘joke’ (which of course cyclists reading it failed to ‘get’ for some reason) took an equally familiar turn.

Hatred against cyclists has often been compared by some people who cycle, and who feel themselves regularly on the receiving end of it, to systematised bigotry which targets legally protected characteristics, such as their sex, sexuality, race and so on. Such legally protected characteristics, the standard response (as trotted out by Cristo here) goes, are, however, given. You’re either female, African-American, lesbian or not. Hence you cannot compare hatred directed against members of such groups and that directed at, say, cyclists – who happen to choose to cycle. Remarks like those made by Liddle or Cristo or even the ‘gay-lycra-pedo-nonce-roadlice’ crowd about cyclists are not therefore comparable to remarks directed at someone because of their protected characteristic(s). So if you object to such remarks about cyclists by invoking comparisons to racism etc. you’re just clutching your pearls.

Having prodded the hornet’s nest again, in order (a cynical observer might suggest) to keep bagging those sweet, sweet tweet impressions and thus getting paid, Cristo is, in his insistence that a joke’s a joke and prodding cyclists isn’t racism, epically missing the point (any possible bad faith aside).

As a wise woman once said to me (last Saturday night, actually), focusing on whether cyclists have particular characteristics is the wrong focus. What matters is the nature of the negativity directed at them, and what effects it has. Making cyclists themselves the focus of any debate is a bit like the victim-blaming response to road-safety, which demands vulnerable road users do more and more to make themselves ‘visible’ rather than demanding drivers be trained properly. The problem here is not whether hating on cyclists is somehow directly comparable with racism or homophobia in terms of the nature of its target. The point is that hatred directed against people who are visibly members of a group that’s judged to be ‘deviant’ and therefore an ‘out-group’ by some more socially dominant ‘in’ group can lead to actual violence and harm – whether the basis of this judgement is some protected characteristic or not. And this is obviously more the case if members of that dominant group have significant means of inflicting that violence and harm (such as being behind the wheel of a 2-tonne SUV).

Consider the the murder of Sophie Lancaster. Sophie and her boyfriend were attacked for their chosen style of dress (they were identified as ‘moshers’ by another group). Sophie died as a result of her injuries. As a teenage goth myself, I remember very well being chased by gangs of casuals (who beat up a couple of friends who did get caught) simply because I had chosen to look different. I remember the fear that hovered over any trip into town on a Saturday, or to the local rock club on a Wednesday night.

So forget Cristo Foufas’ talking points: what happened to Sophie Lancaster demonstrates that hatred doesn’t need to target legally-protected characteristics to be dehumanising, fear-inducing and also potentially deadly. But we can point to another analogy that underlines just how determinedly Cristo and his fellow ‘jokers’ are barking up the wrong tree.

People on bikes are, in many ways, in the same position that football fans were in the 80s. The Hillsborough disaster on 15 April 1989 killed 96 football fans, when catastrophic decision making by the police combined with dangerous steel crowd enclosures to cause a lethal crush at one end of the ground. It came at the end of a 20 year period in which football supporters had been increasingly vilified as violent thugs, as the worst kind of deviants. After the disaster, vile lies were spread in the national media and most famously in the Sun newspaper, which had played a significant part in stoking anger and fear towards football supporters in the preceding years. The Sun reported that fans at Hillsborough had urinated on police officers trying to help the injured, and had pickpocketed dead and dying fellow supporters.

None of that was true. What was also inaccurate, and had been for many years, were perceptions about the scale of the ‘hooliganism’ problem that British football had allegedly been suffering from. Phil Scraton, who wrote the definitive book about Hillsborough (Hillsborough: The Truth, quoted below from the 2009 edition), noted how much the issue was overblown.

The 1984–85 season, the focus of the Thatcher Government’s zealotry over football violence, had an arrest rate of 0.34 per 1,000 attending matches with a joint arrest/ejection rate of 0.72 per 1,000. Over the following season, while ‘hooliganism’ was catching the headlines and hyping political imaginations, the arrest and ejection figures dropped by 51 per cent and 33 per cent respectively. The figures remained consistent over the next few seasons leading the newly formed Football Supporters’ Association to conclude that ‘many fans’ considered the problem of hooliganism to be ‘overstated . . . the average football stadium does not become a battleground on Saturday afternoons’.

Scraton, 2009, p. 33.

Nonetheless, ever since the Wheatley report in the early 70s, football fans (and young, male football fans in particular) had been assigned to a despised and feared out-group. Steel pens of the kind used at Hillsborough began to be deployed in the UK in 1974, a reflection of a sense among politicians and police that the ‘problem with football’ was essentially one of crowd control. Following the Heysel stadium disaster in 1985, this dominant approach to dealing with ‘the problem’ intensified. Scraton again:

Politicians, journalists and academic researchers seemed caught in the headlights of hooliganism, their gaze transfixed on crowd control. Crowd safety and the ever-present danger of unsafe grounds were virtually ignored. With crowd control and policing viewed through the lens of hooliganism, important issues of corporate responsibility and duty of care rarely featured.

Scraton, 2009, p. 30

Scraton goes on to point out that, at Hillsborough, “the risks were known and the fatal crush in 1989 was foreseeable”. This was following previous crushes at different grounds through the 70s and 80s, and also at Hillsborough itself. The use of metal fences to divide the Leppings Lane terrace at the ground into pens made “a demonstrably unsafe terrace dangerous”. Ever since the Wheatley report, which had investigated the deaths of 66 fans at Ibrox in 1971, keeping potentially dangerous members of a deviant, irrational group contained and separated from other members of that group was the sole purpose of football policing. The senior officers in the control box, like officers in the ground, did not anticipate disaster because they were looking for trouble, but solely through the lens of hooliganism. (Scraton 2009 p. 67)

Scraton’s argument is that football fans died at Hillsborough because they were put in a particular box, that of a deviant out-group, which led to them being put in literal boxes, the steel pens which helped to kill them. Being a football fan isn’t a protected characteristic. But that doesn’t mean they weren’t treated as subhuman, whether through their treatment by the police, or in subsequent media commentary. After Hillsborough, Peter McKay wrote in the Evening Standard that football fans were victims of the ‘mindless passion, rage and violence that soccer attracts’. Auberon Waugh made up 3,000 Liverpool fans ‘rioting outside the gate’, many ‘without tickets’, having ‘spent the time drinking.’ Ticketless Liverpool fans were ‘further excited by the prospect of not having to buy tickets’ and ‘charged in’. Examples multiplied, from the Liverpudlian and Mancunian local press to the Daily Star and other nationals. It was all based on untruth, and on longstanding prejudice which, as Scraton points out, was completely at odds with the reality of ‘hooliganism’.

Hillsborough provides a perfect example of what hate, born out of derision, disgust and fear can do, even if the target of that hate is a group of people who have just chosen to be part of it. Media-fuelled ‘bigotry and prejudice’ (Scraton, p. 158) across two decades – the continuing obsession of newspapers and TV with the alleged deviance of a specific and visible out-group – contributed directly to the deaths at Hillsborough. Without first-hand experience of watching football, most people relied on newspapers as their only source of

information. Fear of and contempt for fans was widely shared. The stereotype of the violent English football hooligan was shared worldwide.

Now back to cycling, and to those like Cristo who think cyclists protesting at what they identify as hatred is a step too far.

Sophie Lancaster’s murder shows this is false, and but so does Hillsborough.

In football, perceived deviance led to prejudice, which led to policing practices and football grounds that killed football fans. With cycling, media-fuelled anger and derision, coupled with violent oh-so-tongue-in-cheek fantasies of people like Liddle and Parris, and the publicity-hungry prodding of Foufas et al, creates an atmosphere in which building protected cycle lanes is opposed at every step. Often, the opponents are people who decry cyclists as all red-light-running lawbreakers who ‘will only ride on pavements anyway’.

In the 80s, the majority of people didn’t have direct experience of being a football fan, and how it felt to be treated and corralled like an animal. Most people don’t know what it’s like to be a ‘mosher’ and spend your days on the receiving end of contempt and the ever-present threat of assault from people who’ve never previously met you. Most people don’t know what it’s like to commute, shop and travel for everyday purposes by bike. And so most people don’t know what it’s like to feel the constant threat of the close passing driver looming over your shoulder, and then come home, go on the internet or listen to the radio and be confronted by the monotonous drum beat of ‘jokes’ about how terrible all cyclists are, and read endless opinions about how, when cyclists die in collisions, it’s invariably their fault. Or perhaps (tongue-oh-so-firmly in cheek, of course) that they should just be killed.

Widely-shared, culturally embedded prejudice against football fans killed 96 people at Hillsborough. Widely-shared, culturally embedded prejudice against ‘moshers’ killed Sophie Lancaster. And widely-shared, culturally -embedded prejudice against cyclists regularly kills cyclists. Research is beginning to show that when you spread, facilitate or provide a forum for anti-cycling prejudice, you’re not just cheekily ‘offending’ someone (with a wink to your chosen in-group), you’re actually helping to endanger cyclists. Because people who express negative feelings towards cyclists are actually more likely to behave more dangerously towards them.

So Cristo, Liddle and others may protest all they like that it’s all a joke, and then respond to criticism by denying that ‘jokes’ about cyclists are comparable with racism or homophobia.

But all of that is absolutely irrelevant.

Look elsewhere for an appropriate comparison, and it becomes apparent that there’s no reason to treat the effects of anti-cyclist prejudice as any less serious than the effects of prejudice towards football fans on those fans at Hillsborough in 1989. Like those fans, people on bikes are collectively blamed, denied safe infrastructure, and finally vilified when they die.

This is brilliant. Will share on all my channels.

T

Cheers!

Thank you. This perfectly sums up the effects of the cyclist haters, who aren’t allowed to spew their bile about race or sex any more, so focus on an out group that isn’t protected. Has Cristo been approached for a comment.

I too will be sharing this as widely as I can.

Thank you! I did share the link with him once. Don’t think he read it. Is a busy man after all 😀